The mahaguru was very particular about leading a debt-free life. He did not accept anything he could not afford. He was also wary of taking or consuming salt or cereals paid for by another. However, a few stray incidents made me realise that he valued intent above obligation.

Bittu ji described a memory from his trip with Gurudev and a few others when they travelled from a soil survey camp in Himachal Pradesh to Gurgaon via Karnal. Kasturi, the mahaguru’s driver, was concerned about driving at night and asked if they could spend the night at a gas station en route to their destination. Kasturi’s cousin ran the gas station, and he knew his guru would feel at ease there.

When they arrived at 11 pm, Gurudev informed everyone that they would leave at 6 am the following day. The gas station owner’s family arrived an hour before the mahaguru’s scheduled departure time with a freshly made breakfast of hot puris, subzi and chai. Although tempted, the mahaguru’s disciples refused because they did not want to be obligated. On the other hand, Gurudev graciously enjoyed the breakfast, making the owner feel appreciated. He knew that to prepare such a lavish spread for such a large group, the family must have woken up at 3 am, worked until about 4 am, and then driven for an hour to arrive on time. He did not pay for the breakfast but certainly reprimanded his disciples for neither honouring devotion nor valuing intention over obligation.

Decades ago, after a long roundabout cab ride, I reached the Mungaoli camp only to be greeted by Gurudev and some co-disciples as they were finishing dinner. I had carried a packet of pakoras with me from the train station. Since the cabbie had ensured that dusk morphed into the night before I arrived, I silently set the pakoras aside. As I headed towards the food tent the following day, I ran into Gurudev juggling two pakoras before munching them. Upon greeting him, I told him he had to pay me for those as I had bought them. “Is that so?” he asked and ate another as he walked away. The morning antics of a great guru can engulf you in a tornado of thoughts! I had purchased the pakoras thinking it was my guru, not me, who was buying them. It occurred to me that eating the cold pakoras was his way of repaying the sentiment of total surrender.

Repayment for thefts, even if petty, came in only one way – reprimand! Once as I chatted with Gurudev while he dressed for work, he looked at his wallet and noticed a few bills missing. He mumbled under his breath and casually mentioned the name of the person who probably stole the money. I asked him why he wasn’t calling out the guilty. He said it wasn’t required since that man would lose the benefit of some of his seva. The amount stolen was paltry, but the loss of months, if not years, of seva, was substantial!

I’ve been a victim of a ‘lost in Gurgaon, found in Mumbai’ experience. It happened like this. I was at the Gurgaon sthan when Gurudev suggested that my wife and I fly with him to Hyderabad for a wedding. All I had was 6000 rupees in cash, plastic money being uncommon at the time. Undertaking that journey would have cost far more than I could afford, so I sent Gurudev a message requesting him to allow us to travel by train instead. I did not receive an answer from him all day but noticed that my wallet had gone missing! On approaching him to apologise and seek forgiveness, I saw a mischievous glint in his eyes. He told me I should always do as asked and not analyse his instructions. A few days later, I found 6000 rupees in my blazer’s pocket at home in Mumbai. Aha! The mahaguru could wing any situation at will and even use paper currency as origami!

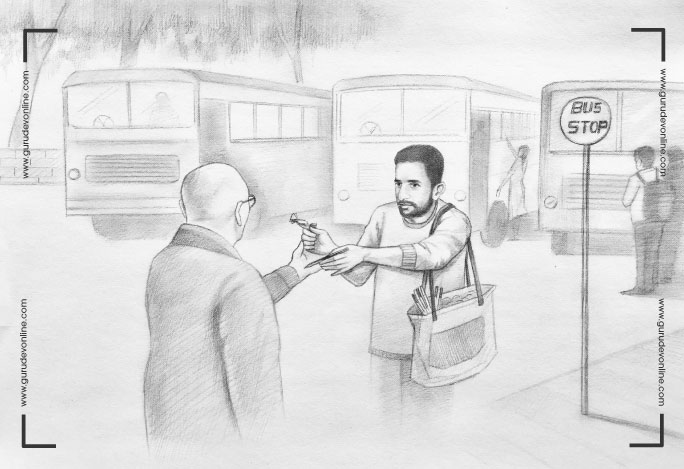

Gurudev struggled to make ends meet when he first moved to Delhi from Hariana. He sold toffees, pens, and bus tickets, sometimes making enough to buy two bananas in a day. Despite the adversity, he was clear that money had to be earned and not misappropriated.

Young Gurudev sells toffees and pens to make ends meet

At the age of twenty, he got employed as a soil surveyor and started spending several months at camps in the hilly interiors of Northern India. According to Nagpal ji, “He would go to every stretch of land to examine the soil and was not bothered by terrains that were challenging to navigate. He would not write his report unless he had personally analysed the soil samples”. The mahaguru justified his salary and made no concessions in terms of effort. Whoever thinks great gurus have it easy must examine Gurudev’s life!

His painstaking labour earned him a pittance at the end of each month. His starting base was as low as 150 rupees, yet he distributed a significant portion of his salary on payday to those in need. There was no process of selecting such people, but he shared whatever amount he thought would meet their requirements depending on their problems. Other than him, I have not heard of anyone being broke on payday despite having worked tirelessly through the month! However, as the mahaguru’s family grew, his disciples learnt to smuggle at least half of his salary to his wife.

Gurudev regarded money as a tool of spirituality and not a measure of materiality. He hardly ever spent money on himself and wanted his disciples to understand its value. When Bittu ji purchased an expensive tray on which food could be served to his guru, he only managed to irritate him. The great guru reprimanded him, saying, “It is not in our disposition to be ostentatious and given to luxury. We must value simplicity and not show off”. Even a simple item like a tray, customarily considered a necessity in household kitchens, was taken as a symbol of luxury by the guru. In his dictionary, frugality took on a whole new meaning.

He always told us money earned in proper ways would find an outlet for good use while that earned by improper means would be squandered in some form or another. When Santlal ji bought two lottery tickets, he presented them to his guru with the selfish aim of obtaining his blessing to win the lottery and enter the draw into the Himgiri Trust, established by Gurudev to manage the sthans. The mahaguru tore the tickets in two, saying, “I think of my disciples as my lottery. Whatever seva happens via the Trust will be funded by their hard-earned wealth as I have enabled them to earn their seva.”

Whenever he allowed us to spend any money at the sthan, it was always for the seva of others. There was expenditure on days when the public came to see him, and a few disciples were allowed to contribute. He hosted several marriage ceremonies at the sthan, and while these were simple affairs, he permitted some of us to contribute minimally towards the cost of the weddings. Many affluent people would have been happy to donate substantial sums towards public welfare, or for that matter, even Gurudev’s upkeep, but he refused to entertain them and sent them packing. Neither money nor gifts were accepted from people who visited the sthans. Their good wishes, however, were welcome.

His disciples and devotees came from different walks of life and earned differently from each other. Yet, he equated them on spiritual intent and gauged them on a line of future continuity rather than the dot of present existence they measured themselves on. At the sthans, bus drivers and business tycoons were treated alike. When the great guru was constructing the sthan at Sector-10 in Gurgaon, he allowed his disciples to contribute. From those permitted to contribute, the less financially able were asked to contribute 100 rupees each while the rest could give slightly more. Even though the contributions were as per affordability, the benefit of the seva was equal.

A Sikh gentleman once came to see Gurudev hoping to be permanently relieved of a chronic headache. “Son, I will cure you immediately”, the mahaguru said, “but you must abstain from non-vegetarian food and alcohol from now on”. Two weeks later, this man returned, carrying a briefcase with a hundred thousand rupees in cash. He prostrated before the guru and kept the briefcase by his side, imploring him to accept a token of his gratitude. The unaffected guru looked him in the eye and said, “As soon as I touch the briefcase, your headache will return. It is my duty to do seva, not my business”. The sheepish Sikh thanked the mahaguru and returned home with his unopened briefcase.

Greed for money, defrauding people of their wealth, or luring them with the promise of business or monetary gain were habits that the mahaguru condemned. A senior disciple who had inherited some property was greedy for more and willing to engage in domestic politics to obtain a larger share from his maternal grandmother. His pettiness was also evident in other minor ways. The astute mahaguru was aware of this flaw in someone who would graduate to becoming one of his most accomplished disciples years later. He recognised the disciple’s habit needed correction and subtly explained the distinction between the worthiness and worthlessness of money. “Don’t crave for money because I will give you so much spiritual wealth that you will never run out”, he told his disciple.

Flaunting wealth or gambling it away was also taboo in his playlist of commercial hygiene. During Diwali, when most people bet on money, he taught us to respect it, saying it was the gift of barkat from Laxmi Devi. Disrespecting money was akin to disobliging the deity.

In his view, the money we spend on ourselves or allow others to spend on us creates a debt, whereas that we spend in the service of others credits us with the benefit accrued from the act. More importantly, money can supplement but not substitute spiritual intent. One of the mahaguru’s recommendations was to deploy 10% to 20% of our monthly earnings on seva.

PREV << SOCIAL HYGIENE

NEXT >> MENTAL HYGIENE